Hello and happy Monday!

The music scene for the week ahead

I sat and thought about my rant last week and realised that it’s sometimes hard to acknowledge when to stop and take some rest. I believe in intuition, and I think it’s sometimes working hard to draw my attention to things. When I’m tired, I become deaf to it. So for the sake of my balance and intuition, I’ve taken next week off; I plan to return to the books I’ve been neglecting. Isn’t it nice that they never blame you for putting other things first? They’ll be right where I left them, and so will the bookmarks in them. 💙

This past week, the music system in our house, usually left on shuffle mode, has been playing an alarming amount of Christmas songs. And with my parents visiting, who watch regular, live TV, I had no choice but to sit through tens of minutes of commercials: some have already started using Christmas jingles.

I am not feeling it yet. Of course I’m not! It’s not even the middle of October yet!

I remember last year that I didn’t feel the Christmas mood until very late, probably not even while decorating the tree, which we decided to do on December 1st. Between the 1st and the 25th, it felt like an entire other year had passed.

I haven’t even started High Fidelity, but I am already looking forward to reading Harry Potter in December. I’m convinced it will put me in a Christmas mood pronto!

Jonathan Franzen’s new book, Crossroads, is out

Jonathan Franzen is one of those writers that I have heard so much about that I have to stop and think if I have read anything by him.

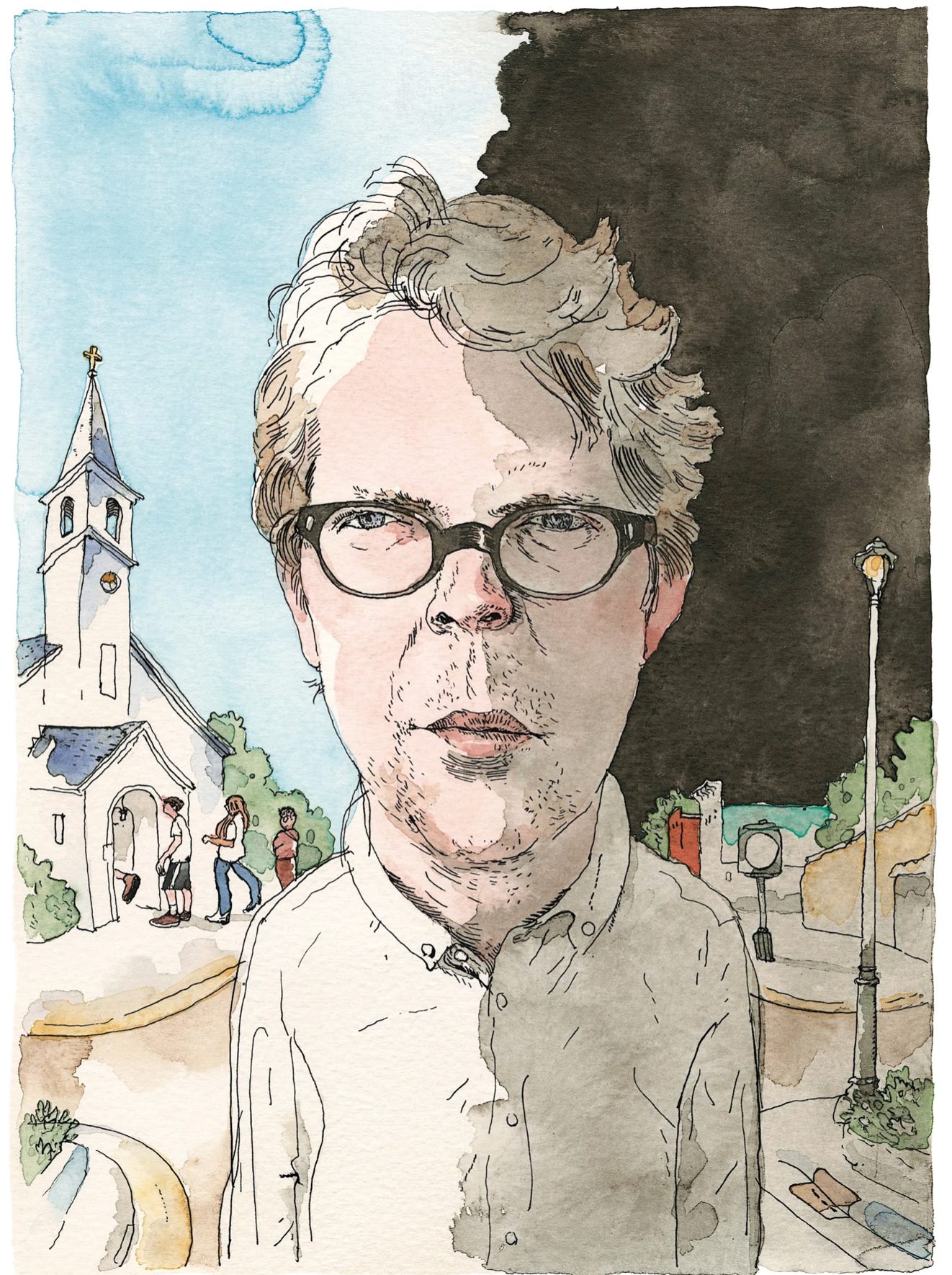

It turns out I haven’t, but I would like to! I’ve heard of his name around the same time as Jonathan Safran Foer, and I kept confusing the two for a long time. While I’ve read and met the latter (can you say that when you only shake hands and take a photo?) I had a blank image of the former until I saw the illustration above from The New Yorker.

A rabbi, a preacher, and a drug dealer walk into a Christmas party. This is not the setup to a joke; it is the setup to a pivotal scene in “Crossroads,” Jonathan Franzen’s new novel. (…)

The distinction between real and ersatz virtue is the central preoccupation of “Crossroads”—so much so that Franzen, who historically wears his thematic concerns on his dust sleeve (“Freedom,” “Purity,” “The Corrections”), might have titled this new novel “Goodness,” if the word didn’t double as an awkward exclamation. It is true that “Crossroads” is also concerned, like every Franzen novel, with the makeup and the breakdown of American families. And it is concerned, too, with the issues implied by the title he gave it: those moments in the lives of individuals and in the history of a nation when stark choices with permanent consequences must be made. But, deliberately and otherwise, the book returns again and again to the same question: What does it mean—for a person and, in a different sense, for a novel—to be good?

The New Yorker, October 4th, 2021

Genre fiction vs literary fiction

Here’s something that I know I am guilty of myself, despite having been proven wrong time and again: judging a book by its genre when that’s not the whole story.

Right off the bat, I want to say that this genre vs literary fiction thing itself is a surprise to me, too. I hadn’t realised there’s something called “literary” fiction that sits outside genres 🤭.

For this, I miss the times when books were an unknown: you picked them out, usually solely based on title, because everything else was hard to get to, and you were in for the ride. I remember the old books at the university library, so worn out by generations of students that they had to add new cardboard covers to make them more sturdy. They were usually grey, and you’d have to open them to see what book you were holding in your hand.

Genres became too restrictive and too niche, in my view. I remember reading Stieg Larsson’s trilogy before Scandinavian Crime was a genre. Then again, I spent some time looking for similar books because I wanted more.

And yet, there’s no better example than Stephen King and what his writing is to me to illustrate how genres don’t show the whole picture: to me, he’s not a horror fiction writer, he’s not a crime story writer, he doesn’t write magic realism or supernatural stories, but I wouldn’t say it’s realism. And yet he’s been put in all those boxes many times. I think his book, 22.11.63, was labelled as historical romance, although I dare you to read it and tell me that’s the genre you would attribute to it!

I came across this article, which touches on another pertinent element of all this conversation: snobbery!

The article starts with his own mocked attempt at “gender-bending” when he wrote a tagline for his debut novel, which I haven’t read but which he described as “science fiction body horror baseball noir novel.”

It’s interesting to see the array of genres that users picked on Goodreads and The Story Graph.

If you’ve got a few hours to kill, ask a SFF fan to delineate the differences between “cyberpunk” and “steampunk” or “epic fantasy” and “grimdark.” On the other hand, the scars of decades of genre wars, two-way gatekeeping, and general snobbery leads many people to throw up their hands and say “It’s all just marketing! Art doesn’t need labels!” (…)

But while it’s important to break down the barriers of snobbery between genres, I don’t think we should flatten them to mere marketing labels. Genres are vital artistic traditions, with their own aesthetic histories, concerns, and modes.

Lincoln Mitchel, on Lithub.com

I particularly like the author’s analogy with genres being like people at a party:

Imagine literature is party in a grand estate. Countless people seem to be there, and more keep arriving. It’s loud and chaotic and exciting. Within this party, different groups of people cluster to talk. Some in fancy costumes chat in the rose garden. Others mutter in the library or laugh together beside the graveyard plot. In each of these different conversations, people expand on each other’s thoughts, rebut, debate, elaborate.

This is how I like to think of genres. As different literary conversations, ones that stretch back in time and include not just authors but critics, publishers, and readers. When a critical mass forms—and the conversation is large enough—we have a genre. If the conversation is small and scattered, it might be only a subgenre or style. One can engage in these literary conversations to whatever degree one wants. Hunker down in an armchair in one spot for a career or hop around dipping into different conversations as your interests change.

As with any ongoing group conversation, there are sometimes barriers to entry. In-jokes develop. References. Special topics of concern. People who stumble onto the conversation might, at first, be lost. (Typically, it’s good to listen for a while before speaking in literature as in life.) And not every conversation will be of interest to every person. But that’s as it should be. Literature is an infinite and varied place.

Lincoln Mitchel, on Lithub.com

I saw this photo on Instagram this week and felt that it applies to me 100%. Because I have been acutely aware of this, I tried to get into a couple of fantasy franchises different from Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings, and I felt like the third wheel. Lincoln Michel’s metaphor above of conversations happening already when you’ve just dropped in is very much how I’ve felt trying to pick up the pace and gather what I’ve missed out on.

I know this is Adina B’s forte, and because I’m in dire need of escapist outlets, I’m going to be asking her for recommendations for a beginner fantasy-curious. I’ll turn them into a section in our next Grapevine😌

The fun corner: this 😂