Hello and happy Sunday!

Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow

This week has caught me reading the hyped winner of the Goodreads choice awards for 2022: Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin. The more I read, the more I wonder why I keep going.

It’s a very unusual book and it has me intrigued every time I think about how it came to be the most popular fiction read on Goodreads. It is not like anything I have read before, and not because of the way it’s written. It has some nice sentences and images, but other I feel are quite cringy. Like this passage of an incipient sex scene:

“then she put her hand between his legs, wrapping her fingers around the cylindrical chamber of blood sponges that was his (and every) penis.” (Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow, Kindle edition, loc 3229).

The characters are diverse in a refreshing way: most of them are second generation Asian kids who are into video games so much that they’re writing their own and strike it big. One of the main characters becomes an amputee as a result of a gruesome accident that left him an orphan.

They’re lovable by all accounts, but I am failing to see the story holding together. I am not one to usually look for “the point” in a book, but I feel there is something that eludes me about the popularity of this book.

I should have probably started with the title: from the get-go I find it annoying. And so far, I can’t see the connection to the story or anything that is happening. What keeps me going is the hope that I will have an a-ha moment at the end and I will feel bad for all the dissing I’m doing now.

What I keep going back to though is “is this really the best and most popular fiction book on Goodreads for 2022? Really?”

If you’re curious about what got me all conflicted, I’m leaving a review that I haven’t read it (don’t want spoilers or opinions until I’m done reading).

Morally grey characters

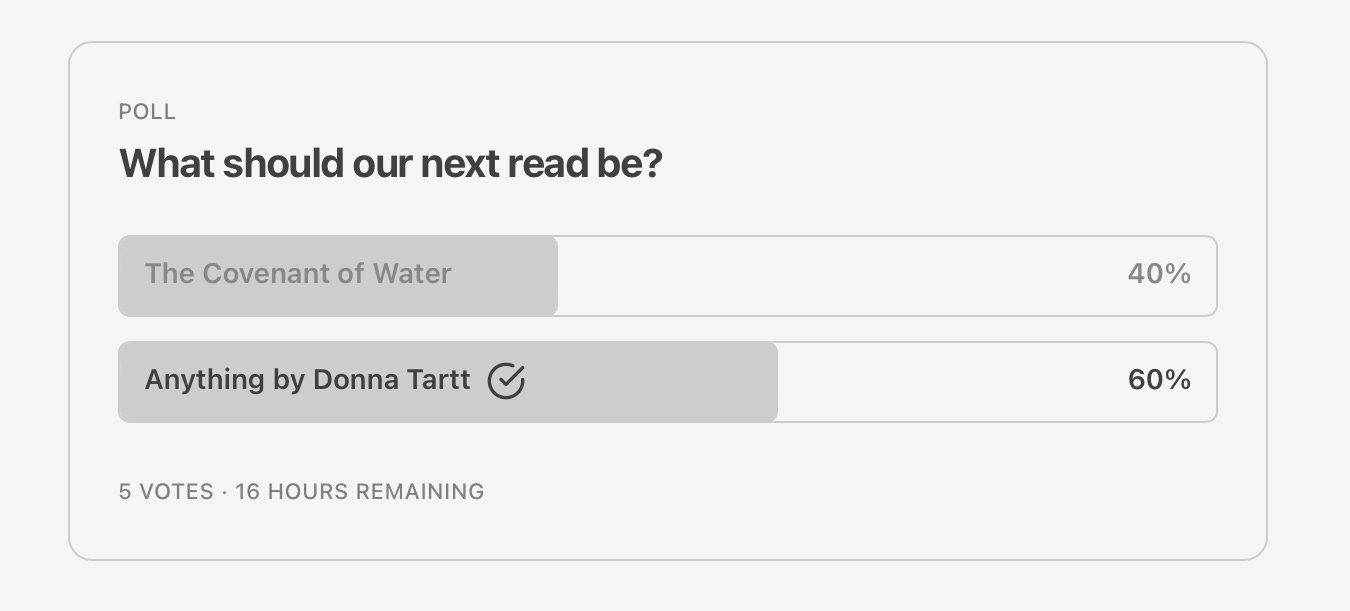

I tried my luck with this poll feature on Substack and you guys didn’t disappoint. If I am holding all of us to it, our next book should be something by Donna Tartt. My obvious choice here would be The Secret History.

I have been long-tempted to read something by Donna Tartt and I am glad we’re finally there. I have no doubt that the conversation will be refreshing especially after the moral ambiguity of Lolita.

Which takes me to the topic of the morality of characters in the books we’re reading. I have been thinking about this a lot, not just in the context of books, but also TV shows. Particularly since for a long time I thought that no one can contest the awesomeness of Breaking Bad as a story and from a character development point of view. That was until I tried to get my husband to watch it, and he couldn’t get past the half point of the first episode.

His reason was that “the character has poor judgment and I can’t root for him.” Whereas for me, Walter White had always had an arc that I found beautiful and entertaining to behold.

Delving deeper into understanding what my husband was looking for in a main character, it turns out he’s very much into the duality of good and evil, with a bit of complexity thrown in there: the villain has to have a big enough and believable driver that it’s not childish or laughable.

Marvel’s Thanos is just that kind of villain. For those unfamiliar with Marvel movies and its plot lines, Thanos is the ultimate villain whose purpose was to bring balance to the universe. How he decides to do that is to randomise halving the population of the Earth thus relieving the strain put on the planet’s resources and slowing down its rapid decline, maybe even regenerating its resources to a significant degree.

The writers couldn’t have done a better job at giving the villain a big enough purpose. Even more so it’s something I can understand, even get behind. The means by which he decides to go about it are what separates him from the good guys. Still, I can understand why he thinks he is doing the right thing: he is randomising genocide and in doing so, he thinks it’s the fairest thing he could do. The good guys who try and stop him have absolutely no hesitation in their actions: they know it’s wrong on all levels.

But what do you do when you’ve got a main character who’s ultimately good, but sometimes makes bad decisions and gets themselves into tight spots? How do you keep a reader (or audience) engaged?

Some audiences might find it too close to real life and thus decide to dump the story for something lighter and easier to digest.

Sometimes I am in that audience. Other times, I am enthralled and I want to see how the writers plot he character out of those situations in a credible way, so I keep reading or watching.

This has been the case with Ozark - the TV show on Netflix - which I am about to finish. With every episode I watch, I am in awe of the writing and the believable development of the characters.

I would liken it in many ways to Breaking Bad. And it turns out, Book Riot looked into the greyness of characters.

They said:

Dostoevsky wrote in his work The Idiot, “Don’t let us forget that the causes of human actions are usually immeasurably more complex and varied than our subsequent explanations of them.” We, as individuals, aren’t good or evil, nor are the people around us. Our life’s experiences aren’t black and white, and neither is the lens through which we view them. So the intentions, actions, and consequences of our choices cannot simply be black and white. All of us live our lives in varying shades of gray. So why shouldn’t our fictional characters be a reflection of our lived experience?

The article goes on to give a few examples, including one of our favourites (was she, though?): Evelyn Hugo.

(…) there’s a line in the book that sums up her moral ambiguity perfectly, “She always made sure the bad was outweighed by so much good. I…well, I didn’t do that for her. I made it fifty-fifty. Which is about the cruellest thing you can do to someone you love, give them just enough good to make them stick through a hell of a lot of bad.”

Why is this important, I hear you ask?

Morally grey characters help us initiate difficult conversations. They are usually a product of the world we’ve built and the one we’re trying to survive in. When a character refuses to work within its rules, we question the rules.

For the whole article, click below.